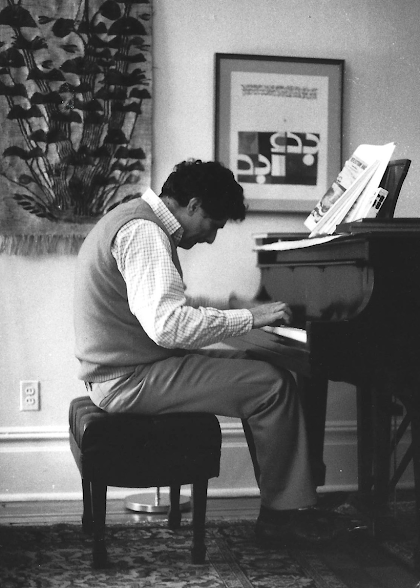

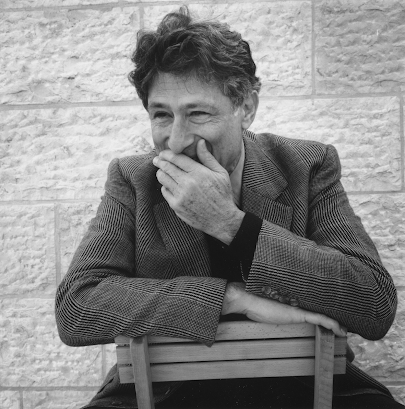

Twenty years ago today, Edward Said finally succumbed to the leukaemia he had so bravely battled for the previous decade. His early death - he was only 67 - was greeted with sadness and dismay by his allies and friends, and no doubt with a grim glee by his enemies. I can still remember getting the news by phone from a scholar friend, and feeling that the world would never be quite the same again.

I've spent much of my adult life reading Said, and, I hope, learning from him. I first became aware of him as a third year undergraduate, when I heard about this book of his called Orientalism, which was represented to me as the greatest Foucauldian book by someone other than Foucault. This was long before the internet or Amazon or other modes of rapid access to books, and my first copy of Orientalism was brought to me by a friend and former teacher from Minneapolis. Now I would say that Orientalism is only superficially a Foucauldian book, but one's knowledge - one's critical consciousness - has to begin somewhere.

A year or so later, I took a Master's degree at University College Dublin, and began to read Said properly. I was very fortunate that teaching me on that MA programme was a trio of brilliant and important scholars - Seamus Deane, Declan Kiberd and Thomas Docherty - who took criticism very seriously, and who thought with rigour and intelligence about what it meant to be, or to try to be, an intellectual. Not merely this but Deane and Kiberd had been crucial to the mediation into Irish literary studies of what we then called 'postcolonial theory': Kiberd, after all, had invited Said to the Yeats Summer School in 1986, and Deane had published the resulting talk as a Field Day pamphlet in 1988. In those days, this 'theory' mostly consisted still in the work of Said and Spivak and Bhabha - postcolonial studies was still something relatively new and radical in the Irish academy and it was not yet a full orthodoxy elsewhere in the Anglophone world. I gravitated to Said most of all - not only because his writing, while never simplistic, avoided the extraordinary obscurantism and neologisms with which the Indian critics larded their discourse, but I also was excited by the sense that, of the three, Said was most clearly an intellectual, an activist-writer who reached and addressed much wider audiences than those of the seminar room.

I read Orientalism with Kiberd, and immediately was compelled by it - the erudition, the wonderful readings it contains (those of French writers such as Nerval and Lamartine and Flaubert in particular), its polemical verve and urgency. I could see, too, how the discourse of 'Orientalism' could be compared fruitfully to that of 'Celticism': that body of colonial themes and ideas which suffused much writing in and about Ireland in the nineteenth century, and which could be politicized by English figures such as Arnold and Froude, and their Irish antagonists such as Yeats and Synge.

But I also independently was reading the book which I now consider superior to Orientalism, and to be Said's masterpiece: The World, the Text, and the Critic. The World, as I'll call it, is a collection of essays Said published between 1969 and 1982, and it's mostly concerned with the politics of intellectuals in the academy. If Orientalism's scandalous success was partly attributable to its steely intervention in the realm of European and American ideas and policy in the Middle East, The World turned its critical weapons on Said's own institution - the university and the discourse of critique. Part of what was so exciting about these essays - 'Roads Taken and Not Taken in Contemporary Criticism', 'Travelling Theory', 'Reflections on American "Left" Literary Criticism' - was that Said could write convincingly about the then-new and vogue-ish poststructuralist scholars in the ascendant in America and Britain - Foucault, Derrida, Lacan, Barthes - while showing himself to be equally comfortable with the themes and ideas of the New Criticism and, even more, the great tradition of Romance philology, whose legatee he could justly claim to be. This was the world of Leo Spitzer, Erich Auerbach, Karl Vossler and Ernst Robert Curtius, extraordinary scholars who helped in the early twentieth-century to invent modern comparative literature. Furtheremore, Said was also imbued with ideas taken from the greatest names of Western Marxism - Lukács and Gramsci - and these in particular helped him work out his devastating readings of the ever-widening gulf between the radical rhetoric of the 'New New Criticism', and its actual and dreary institutionalization and self-reification in journals, curricula, conferences and departments. Said could notice all of this, and call powerfully for what he called a 'worldly' criticism, which was, and is, a criticism which is aware of the relationship between the classroom and the street, and seeks to bridge it and analyze it.

I should admit that it took me a while to grasp fully the implications of this work of Said's, and that I initially read him in a rather instrumental and callow way - when I wanted to investigate Foucault's ideas but recoiled from the difficulty of some of his texts, I turned to Said for a handy gloss. When I wanted to understand Gramsci, I turned to Said for a handy gloss. I would find my interest in cultural geography fired up by his spatialized criticism in Culture and Imperialism, and my reading of Adorno was stimulated by his lucid readings of the Western classical music tradition in Musical Elaborations. Later, of course, I came to realise that Said was always a heterodox Foucauldian, that his geography was insufficiently grounded in the material realities of capital, that his reading of Adorno was arguably incomplete. But I always went back to Said's work and read it again, each time learning a little more, each time maybe understanding it a bit more, and gradually allowing it its own integrity and heuristic power. Said was berated so often by putative allies for being insufficiently Foucauldian or Marxist or, indeed, humanistic, that one came to long for due attention to be paid to the constructive and innovative and effective things he did and thought with Foucault or Lukács or Adorno or Auerbach, and his capacity to conjugate them together. Equally peculiarly, such critique still continues in some quarters, making one wonder just what is at stake in such repetitive polemics. Somehow, Said's putatively sympathetic critics need at once to possess him and to renounce and apparently transcend him and his work.

I became familiar with some of the developing literature about Said's work. I learned from Abdirahman Hussein's splendid reading of the whole oeuvre. I thrilled to Paul Bové's appropriation of Said in his magnificent Intellectuals in Power. I winced at Aijaz Ahmad's withering and doctrinaire critique in In Theory. It dawned on me that Said was, in fact, not a Marxist or a post-structuralist - he'd never toe the line that Ahmad demanded or that Robert Young demanded. Rather, Said was a radicalized humanist, who had realised with Gaston Bachelard that a humanism that did not press itself up to its own limits was not worthy of the name.

It took me a while to read Said's first book, on a writer who obsessed him throughout his life, and who happens to be one of my own favourites - Joseph Conrad. It took me a while, too, to read Said on Palestine: I read the literary criticism long before I read After the Last Sky or The Question of Palestine. I realised immediately, though, how he had brilliantly deployed the weapons he'd acquired as a critic in his political writing - 'Zionism from the Standpoint of its Victims', a major chapter of The Question of Palestine, has to be one of the most impressive instances of the 'worldly' criticism Said advocated so passionately.

Timothy Brennan's biography of Said, Places of Mind, portrayed a fiercely engaged and active life. Reception of the book has not been without controversy - with such a subject, how could it be otherwise? - but I enjoyed it very much. I might have wished for a little more of the private man - someone who clearly lived, felt, acted, argued so intensely, right up to his very last hours, could only be fascinating and intriguing. I myself met Said on a few occasions but could not properly claim to be a friend of his. But his brilliance, warmth, and, in spite of the big ego, his interest in the people around him, no matter their high prestige or complete lack of importance - these were immediately obvious, and wonderful and admirable traits. The world is, as many said at the time of Said's death, a quieter, dimmer, less interesting place without him.

For a while after the death, I wondered what we, what I, could do without Said in the world. And then, with colleagues and friends, and with all due modesty, I realised that the best way to honour his memory was to try to do similar or proximate or affiliated work, and to try to think my way to my own positions as he, autodidact in the style of Vico that he was, had sought to do.

To help with the task of remembering Said today, I am posting five pieces here. Two are my own - my review of Tim Brennan's biography, in the Dublin Review of Books, and an essay commissioned by Dan Finn at Jacobin on Said's worldly intellectual performance. The third article is the excellent and intelligent review of Places of Mind in the Boston Review, by Esmat Elhalaby. The last two articles are the wonderful and heartfelt obituaries by Alexander Cockburn at CounterPunch (which never fails to make me emotional), and Michael Wood at the London Review of Books.

My DRB review of Places of Mind:

Intellectual Insurrection

My Jacobin essay:

Edward Said Showed Intellectuals How to Bring Politics to Their Work

Elhalaby's review of Places of Mind:

The World of Edward Said

Michael Wood at the LRB:

And Alex Cockburn at Counterpunch: